Pre-Colonial Ceramics in Singapore (Before 1819 A.D.)

Fort Canning Hill and Its Historical Significance

On January 21, 1823, Sir Stamford Raffles wrote to William Marsden from his

residence atop Fort Canning Hill:

"The tombs of the Malay kings are close at hand, and I have settled that

if it is my fate to die here, I shall take my place amongst them."

Raffles believed Fort Canning Hill was the residence of ancient Malay kings. This notion aligned with the semi-historical accounts found in the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals).

| View of Fort Canning from mouth of Singapore River. |

Historical Accounts from Sejarah Melayu

According to the Sejarah Melayu, the Malay kings traced their descent to Alexander the Great. One notable figure, Sang Nila Utama, reportedly visited an island where he saw a lion-like creature. Inspired by this sighting, he named the island Singapura, meaning "Lion City," and established a state that purportedly lasted about 100 years under five kings throughout the 14th century.

The Malay Annals attribute the fall of Singapura to Sultan Iskandar Shah, the fifth king, who allegedly humiliated his mistress due to rumors. In retaliation, her father, a treasury officer, helped the Majapahit Empire invade Singapura. The sultan fled and eventually founded Melaka.

An alternative account suggests that Parameswara, a prince from Palembang, became the last ruler of Singapura. After fleeing Majapahit forces, he allegedly killed the local ruler and ruled for five years. He later abandoned the island following an invasion led by the ruler of Patani, avenging his brother's murder. Despite differing narratives, one certainty remains—14th-century Singapore had a thriving community and a ruler, marking a golden phase in Malay history.

14th Century Singapura's role as an entrepot

The discovery of Chinese ceramic fragments in Singapore, similar to those found at other Southeast Asian sites, strongly suggests that the island was a significant entrepot in the 14th century. Its strategic location along the maritime trade route linking East and West enabled it to flourish. Monsoon winds dictated ancient maritime travel, making Southeast Asia an ideal stopover for merchants awaiting favorable winds. Besides trading regional spices and exotic goods, Singapore served as a vital emporium for East-West trade.

Chinese ceramics, especially due to their durability, became key historical evidence of ancient maritime trade. Major maritime powers such as Srivijaya (7th to 13th century), Majapahit (13th to 15th century), and Melaka (14th to 16th century) capitalized on this strategic advantage. Singapore similarly thrived during this period, enjoying a golden era of prosperity.

Archaeological Evidence at Fort Canning

Unfortunately, remnants of Singapore’s early history were largely destroyed. Structures on Fort Canning Hill were demolished during fortress construction in 1859. Additional artefacts were removed in 1926 to build a covered reservoir and later during the construction of the British Far East Command's underground command center in the 1930s. A significant historical artefact, the Singapore Stone, a sandstone boulder inscribed with ancient Kawi script, was destroyed in 1843 for development. Fragments are preserved in Singapore’s National Museum and the Calcutta Museum. The inscription, potentially dating back to the Majapahit era, could have shed light on early Singapore's history.

Excavations and Ceramic Discoveries

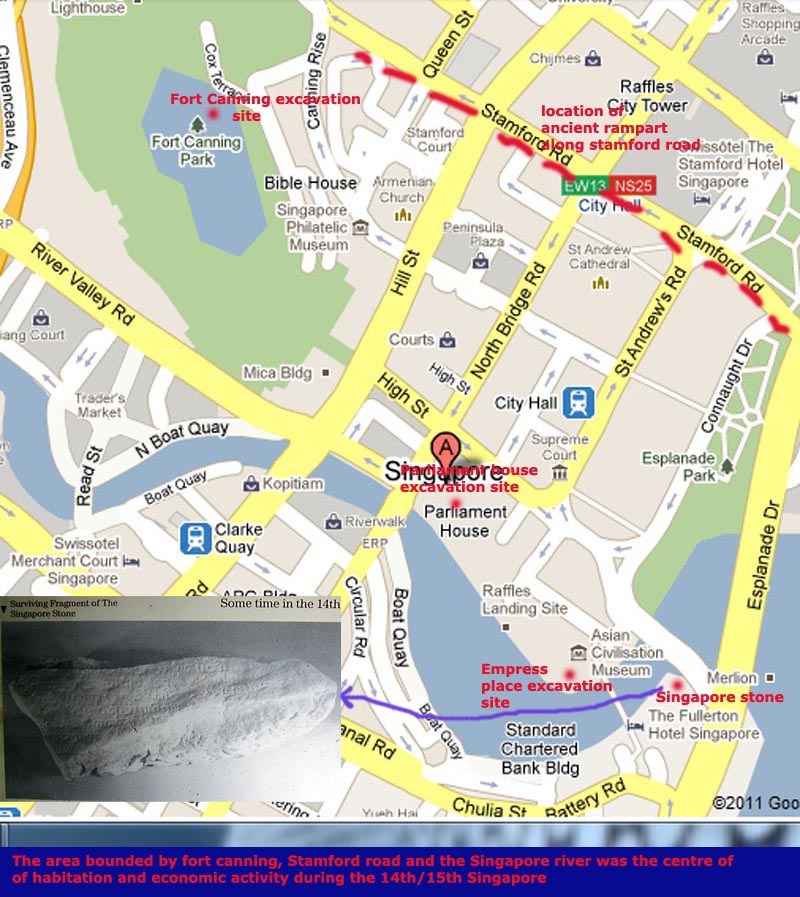

Excavations at Fort Canning (1984), the New Parliament House (1994), and Empress Place (1998) uncovered numerous ceramic fragments and artifacts:

- Fort Canning: The findings, dating primarily to the 14th century, included pottery and porcelain fragments from the Yuan Dynasty, glass beads, and other artifacts.

- Empress Place and Parliament House: While most ceramic fragments mirrored those found at Fort Canning, small quantities dating to the late 15th and 16th centuries were also identified.

These discoveries support the historical accounts of Singapore as a significant trading hub during the 14th century.

|

| Map showing the various excavation sites |

|

|

| Excavation site at Fort Canning |

Chinese Ceramics as Trade Evidence

The large quantity of Chinese trade ceramics found in Singapore provides crucial evidence of its role as an entrepot. During the Yuan period, key ceramic types exported from China included:

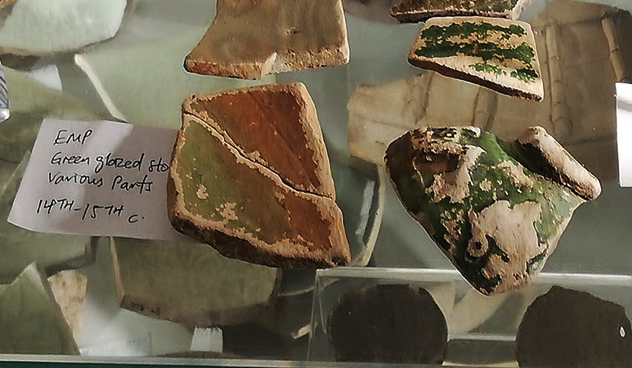

- Zhejiang Longquan Kiln: Green-glazed celadon wares.

- Jiangxi Jingdezhen Kilns: Qingbai, Shufu white, blue-and-white, underglaze copper and iron-brown spotted wares.

- Fujian Kilns: Qingbai, celadon, brown glaze and lead amber/green lead-glazed wares from kilns near Quanzhou.

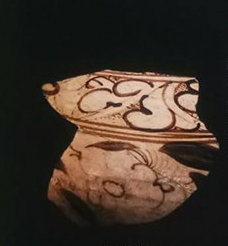

- Hebei Cizhou kilns: Iron-brown painted wares.

|

|

|

|

|

| Some Longquan fragments found in Empress Place and Fort Canning site. | |

|

|

|

| Some contemploraneious Longquan examples found in Indonesia | |

|

|

|

| Yuan Shufu fragments from Fort Canning and contemporaneous examples from Indonesia | |

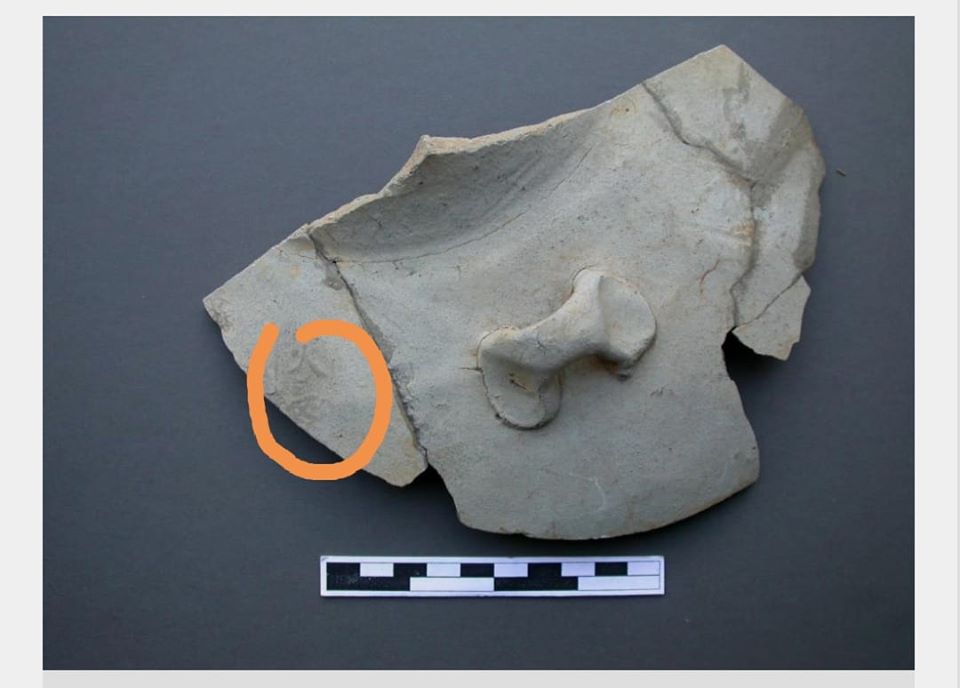

| Remaining fragments of a Yuan Shufu pillow from Fort Canning Site | |

|

|

| Yuan Shufu and blue and white from Empress Place site | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yuan blue and white Yuhuchun vase fragments from Fort Canning site | |

|

|

|

| Yuan fragments with underglaze copper red and iron-brown spotted decoration from Fort Canning site | |

|

|

|

| Yuan vessels with blue and white/copper red decoration from Indonesia | |

|

|

|

|

|

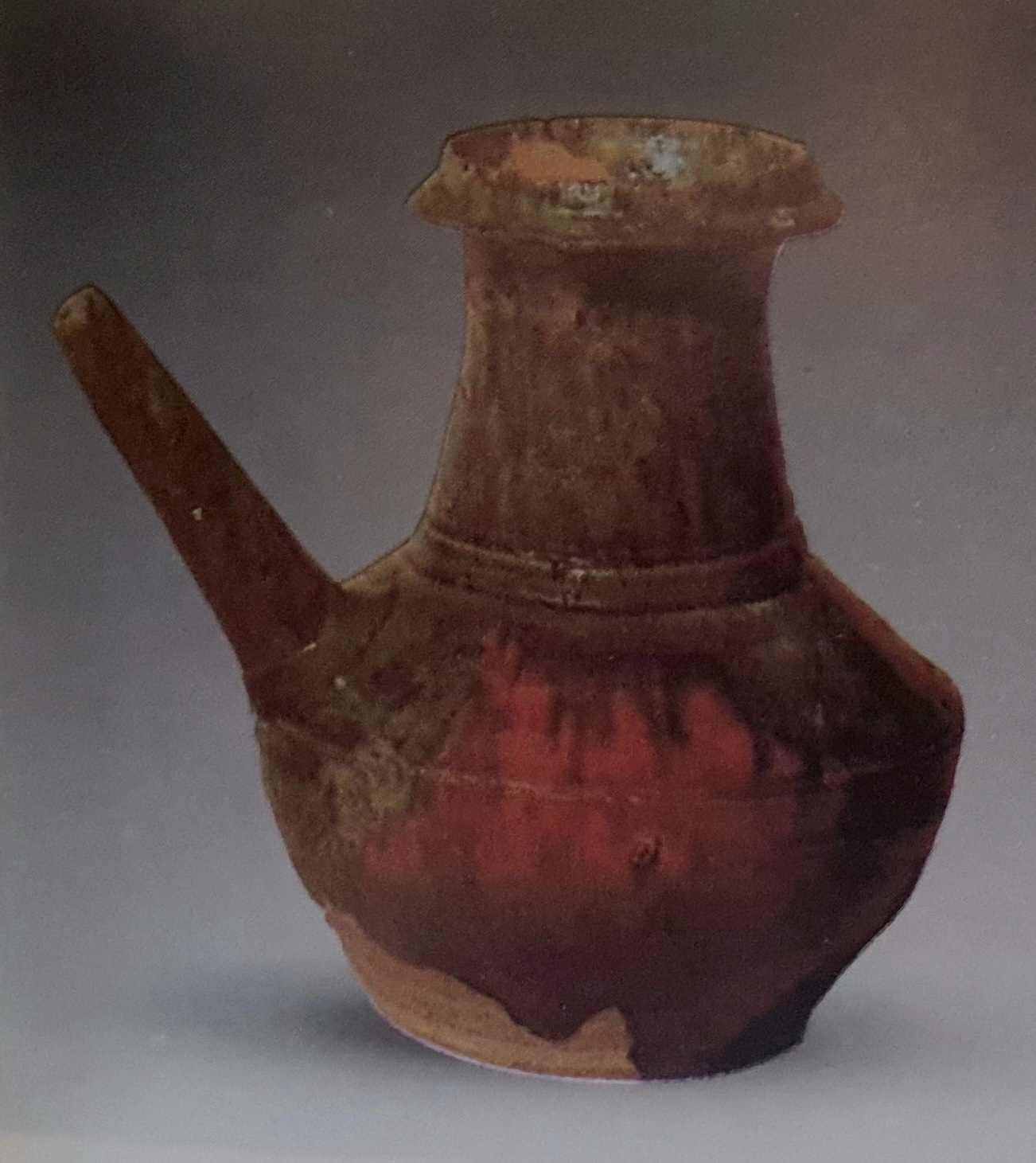

| Fujian Cizao kiln brown jar fragments from Fort Canning site. Recent archaeolgical findings in China suggested that some of the brown glaze jars could also be from Guangdong Nanhai Qizhi kiln. | |

| Yuan Fujian Dehua white glaze fragments from Fort Canning and complete examples from Indonesia | |

|

|

|

|

| Yuan Fujian Cizao kiln lead glaze fragments and two complete examples found in Indonesia | |

|

|

|

|

| A rare Hebei Cizhou fragment with iron-brown decoration. A complete example which indicates that it is from the shoulder portion of a jar. Yuan Cizhou wares are known to be exported and a number were found in Indonesia. | |

Significant Finds

- Compass Bowl Fragments: Found at Fort Canning, these fragments feature one of the earliest known compass decorations on porcelain.

- Huo Zhang (火长) Jar: A 4-lug jar with the impressed characters "Huo Zhang" suggests a link to a Chinese navigator, raising intriguing questions about early maritime activity.

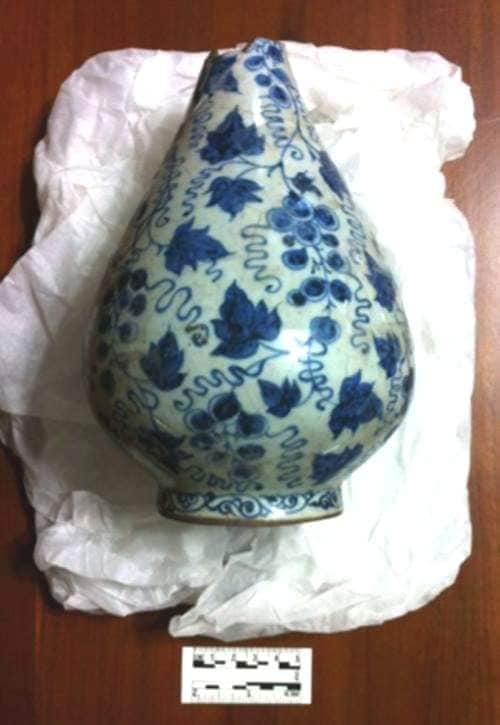

- Victoria Concert Hall: A relatively intact Yuan blue-and-white Yuhuchun vase decorated with grape motifs was discovered in 2011.

|

| Fragments of a Yuan blue and white bowl with decoration of the compass. It is the earliest known example of compass decoration on a porcelain vessel. The earliest written record of the use of compass for navigation was during the Northern Song Dynasty. The typical navigational compass is in the form of a magnetized needle floating in a bowl of water to set the direction. This excavated example has 24 positions as compared with the later version which has 48 positions. |

|

| Jar fragment with the impressed word 火长 |

|

| A relatively intact Yuan blue and white Yuhuchun vase decorated with grape motif from Victoria Concert Hall site |

Decline of Singapura and Nature of Maritime Trade after 14th Century

Following Parameswara's establishment of the Melaka Sultanate, Singapore fell under Siamese dominion. However, Malacca later reclaimed the island from Siam. Ceramic artefacts discovered at Empress Place and the Parliament House complex, dating to the late 15th century, suggest renewed economic activity, likely driven by Singapore's close ties with Malacca, a significant international trading hub.

Despite an official maritime trade ban imposed by the Ming court, large quantities of blue-and-white porcelains continued to be exported. By the Chenghua and Hongzhi periods (1464–1505 AD), the ban had become largely ineffective due to rampant illegal trade controlled by powerful syndicates involving wealthy landlords, merchants, and corrupt officials. Appeals to lift the ban highlighted shifting sentiments, ultimately leading to the temporary lifting of restrictions during the Zhengde reign (1505–1521 AD), which further boosted maritime trade. Evidence of this trade is seen in shipwrecks such as the Lena Cargo, Sta. Cruz in the Philippines, and the Brunei wreck.

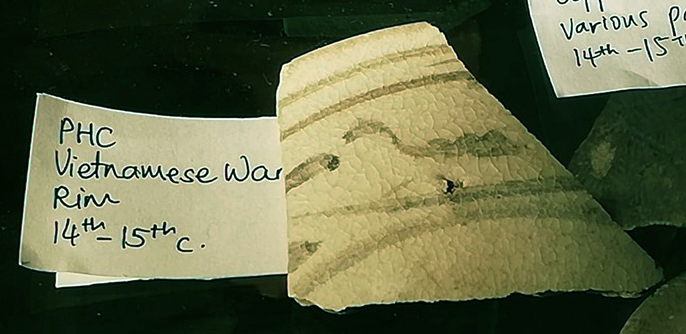

Ceramic fragments from the 15th and 16th centuries uncovered in Singapore include Ming blue-and-white wares, Thai celadon and iron-brown painted wares, and Vietnamese blue-and-white and overglaze enamelled wares. However, the quantity of shards from this period is comparatively much smaller than those from the 14th century, reflecting Singapore's diminished role in the international ceramics trade.

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| Late 14th/early 15th cent. Vietnamese iron-brown fragment found in Singapore Parliament House site. The right is a bowl with the similar decoration. | |

|

|

|

Fragments with mid 16th Cent. Thai iron-black decoration from Singapore Parliament House site |

|

|

|

|

| Vietnamese fragments with 16th Cent. blue and white/overglaze decoration from Singapore Parliament House site | |

|

|

|

| Some comparable complete examples from Indonesia | |

Conclusion

Singapore's archaeological finds reveal a rich pre-colonial history as a significant trading hub in Southeast Asia. The ceramics unearthed provide invaluable evidence of its role in regional and international trade, supporting historical accounts of its past prosperity and interactions with neighboring powers.

Reference:

Early Singapore 1300s-1891 - Evidence in Maps, Text and Artefacts